Life is never easy for a Japanese filmmaker interested in making small, quiet movies. Whether you are Juzo Itami, Naomi Kawase, or Shunji Iwai, any success leads, invariably, to comparisons with the great man himself. The shadow of Japan’s greatest director, and perhaps the most Japanese of Japanese directors, Yasujiro Ozu, looms large over the country’s cinematic landscape and cultural aesthetic. Unlike Kurosawa (too Western in his influences, too taken with himself), Ozu was a gentler, quieter filmmaker. His movies were warm and circumscribed and full of affection. His shadow now looms large, but it grew slowly, methodically, incrementally - each movie adding another brick in the edifice of his greatness (and where later movies recapitulated prior ones).

For any ambitious Japanese filmmaker, the shadow of Ozu must feel like a burden. Or, at the very least, a nuisance. And for all his gentleness, Hirokazu Koreeda is an ambitious and uncompromising director - both artistically and politically. And even a cursory examination of his films leaves you wondering why anyone would make the Ozu comparison - Koreeda is a social realist focused almost exclusively on society’s economic losers. Even before his breakout movie, Shoplifters, he populated his world with life’s deadenders - unemployed painting restorers (Still Walking), pathetic gamblers (After the Storm), abandoned children (Nobody Knows). Ozu, on the other hand, was a resolutely middle class filmmaker focused almost exclusively on middle class concerns. Koreeda himself argues that people in the West have a skewered view of Ozu because, often, the only Ozu film that they have actually seen is Tokyo Story which is very un-Ozu-esque in tone (influenced by Ozu’s bleak and pessimistic contemporary, Mikio Naruse). Koreeda has claimed as his greater influence the British social realist, Ken Loach - and anyone who watches a Koreeda film can see his kinship with the Ken Loaches and the Mike Leighs of this world.

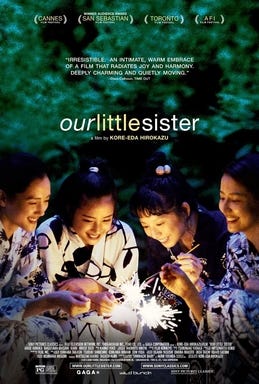

Yet, there was always something plaintive about Koreeda’s rejection of Ozu. Koreeda’s movies are about families and, like Ozu’s, they are warm and humane and accessible. Despite his reputation as an auteur with Hitchcockian control over each project, there is nothing excessive, indulgent nor obscure in a Koreeda movie. Our Little Sister (2015) is two hours long, and yet it feels restrained. And here, finally, the director seems to have embraced his inner Ozu. The movie feels like an homage to the old man, sometimes subtly and sometimes not so subtly. It is set in the seaside town of Kamakura where Ozu is buried, and there is even a scene where one of the lead characters, Sachi (played admirably by Haruka Ayase) and her wayward mother, Miyako (Shinobu Otake) walk up to a cemetery to visit the grave of Sachi’s grandmother. Miayko asks for forgiveness of her dead mother’s spirit - forgiveness for not visiting her grave more often and for not being a good daughter. An homage if there ever was one. And many of the scenes look as if they could have come straight out of an Ozu movie:

The film is based on the serialized manga series Umimachi Diary, and Koreeda does a fine job culling some of the comic book’s excesses. For example, in the manga Yoshino’s boyfriend is revealed to be a high school student (a very manga-esque conceit) and ignored in the film. Suzu’s athletic prowess is also whittled down considerably (although Suzu Hirose comes across as a very credible soccer player). The character of Sanzo Hamada was not so much cast as pulled off the page and given physical form - Takafumi Ikeda was born to play this role. And although not exactly given a free reign, there is some serious talent on display here - including the aforementioned Haruka Ayase whose beauty is almost regal (and who has been often cast, unforgivably, in too many bimbo roles - Hotaru no Hikari, Kodai Family, Honnoji Hotel), and also Masami Nagasawa, Kaho and Suzu Hirose - the latter a limited actress who manages to convince under Koreeda’s direction and in the embrace of her more sure-footed colleagues. Also in the film are the two Koreeda stalwarts - Kirin Kiki and Lily Franky, both of whom in this instance make very brief appearances.

In a grander sense, the message in this film is about the freedom that comes with forgiveness and acceptance. It is a counterpoint to an earlier film, Still Walking (Aruitemo, aruitemo) (2008) which is about the rot that comes with the inability to forgive. It is life’s great irony, I suppose, that by honoring the shadows of the past, you disentangle yourself from it. To respect is to distance. And it says something about a talent as fine as Hirokazu Koreeda that he can work through his own feelings and resentments as a filmmaker and still produce a work that is not in the least self-absorbed.

A review of Our Little Sister, of course, cannot ignore the “tunnel” scene:

How rare is this in film, how impossibly difficult it is to capture a moment of pure contentment, an exquisite piece of modern filmmaking. And notice the sakura petal caught in her hair for the duration of that moment before it floats away. Real contentment comes when you give up on old grievances and long-held resentments. And note how Koreeda captures that moment through movement. No eye-level static shots, no fixed cameras, no wooden formality, unchanging, unyielding. Contentment comes with freedom in the form of movement - a moving crane shot, a backward tracking shot and a lateral tracking shot - breaking free from didactic manners in a breathtaking tunnel of chrysanthemum. Yasujiro Ozu would not have approved.